Introduction

I'm a bit late to the party when it comes to commentary on Nate Silver's book the Signal and the Noise1, but I recently finished reading it and I have a lot of thoughts about it.

Main Ideas

First, I want to say that I think it is an amazing book that is worth reading for anyone who is interested in statistics, practitioners and laymen alike. If you are considering reading it (and are reading my blog for some reason), I highly recommend it.

The main goal of the book is to investigate why "a vast majority of predictions fail" and to provide some tips to make better predictions.

In the book, Silver discusses various case studies where predictions either fail or succeed, and explains the reasons behind these outcomes. This deep dive into each of the several subject areas he looked at focused on aspects of their systems that made them difficult (and sometimes impossible) to predict reliably using models, as well as the approaches that the model creators took when trying to generate predictions.

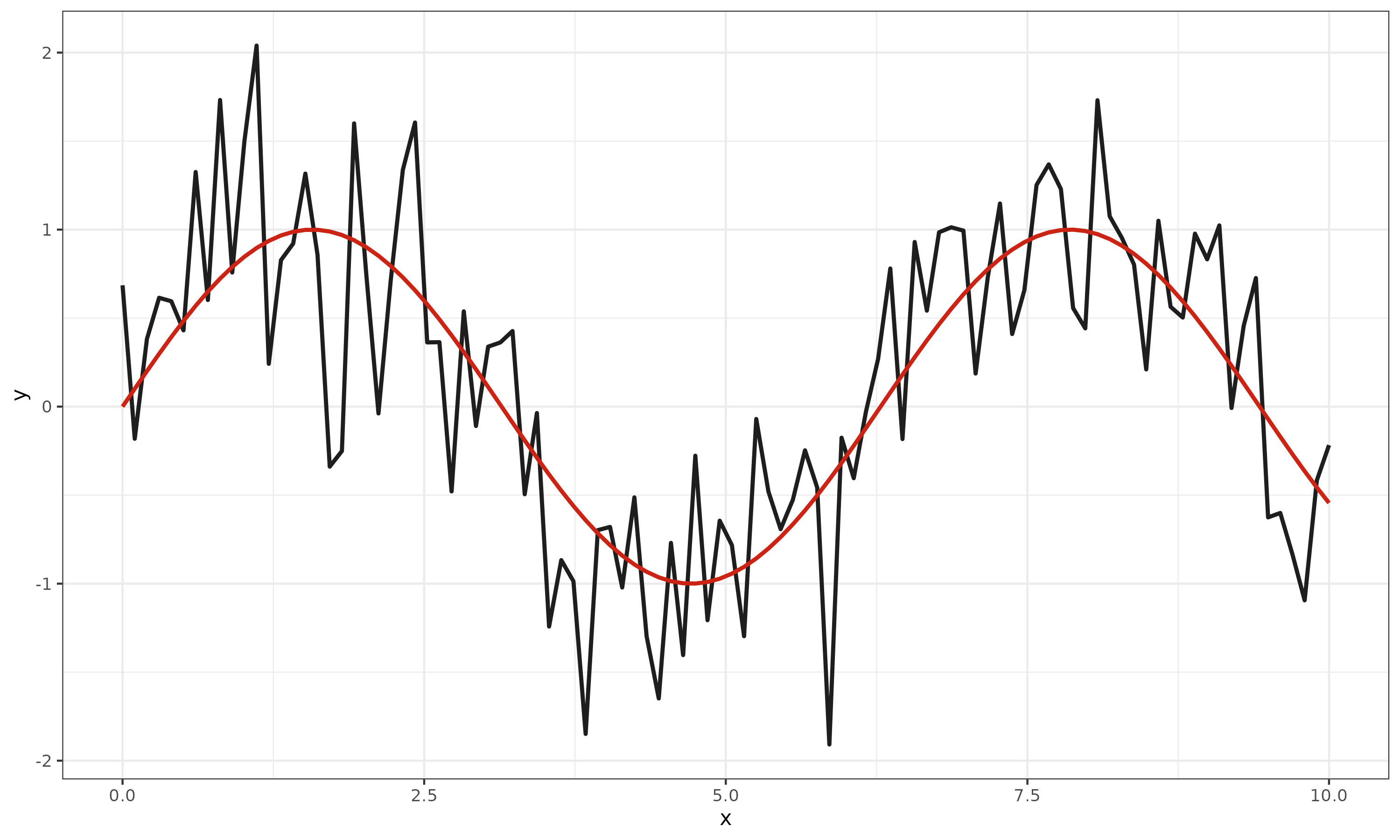

In his analysis, he repeatedly highlights a tendency for modelers to mistake noise (meaningless patterns present in the data) for signals (meaningful information we seek to extract and understand), leading to very poor predictive performance.

This tendency was especially common in fields where data is particularly noisy, or where signals are formed by extremely complex interactions between many different variables. In particular, he highlighted earthquake and stock market modeling as examples in which countless people have tried (and failed) to create reliable predictions about the future.

Another important observation Silver made was that a common cause for bad predictions is the tendency for people to make predictions in accordance with the "herd mindset". In cases like making predictions about the stock market or economy in particular, this tendency is very common, and can often result in bad predictions when the herd tries to be too safe or is too slow to adapt to broader environmental changes. When predicting economical swings, adhering to the herd has few downsides, whereas veering away can have dire consequences to someone's livelihood, especially if their prediction is wrong. Silver notes that this is because staying in the herd when predictions are wrong means everyone is wrong, whereas leaving the herd leaves you exposed without a herd to hide behind. While this can sometimes be good at preventing mass panics, this also has the unfortunate effect of disincentivizing astute analysts from showing off their findings, on the off chance they are wrong.

He also highlighted cases where reliable models for prediction have been established--namely in baseball and weather forecasting--by finding ways to overcome the noise.

I found these chapters to be especially interesting, as both fields involved a vast set of different challenges that had to be overcome, with both fields eventually overcoming these challenges and producing impressive predictions (that we often take for granted in the case of the forecasts).

The story of how predictions finally started succeeding in weather forecasting stuck out to me as it is a problem that humans were trying to solve for hundreds (or thousands) of years, and we were only able to reliably do it in the last 70 through the convergence of many different fields (meteorology, physics, mathematics, statistics, and computing).

In the back half of the book, he provides suggestions for how to make better predictions, passionately advocating for a much wider adoption of Bayesian statistical methodologies instead of traditionally used frequentist methods. This advocacy for Bayesian reasoning and inference is the main driving point throughout the book.

Bayesian Reasoning

Bayesian reasoning is a powerful, practical method of translating our beliefs about the world into actionable predictions, in a way that updates our understanding as new information becomes available. By combining prior knowledge with new evidence, Bayesian reasoning allows us to make more informed decisions, continuously refining our predictions to better reflect reality. This approach is very similar to the scientific method, where hypotheses are tested and updated based on experimental data. Both rely on an iterative process of forming expectations, gathering data, and revising beliefs, providing a systematic and intuitive framework for dealing with uncertainty2.

Running parallel to the Bayesian methodology is the alternative methodological school of statistics, frequentism. Frequentist statistics is focused on long run frequencies for(hypothetical) probabilistic events, running in contrast to the Bayesian school which is focused more on single-event probabilities and the process of using and updating beliefs. Both methodologies have their merits, with both having their own strengths, but both I and Nate Silver consider ourselves Bayesians (although I land much closer to the middle than he presents himself).

In the book, Silver takes the stance that applying Bayesian reasoning to the different situations he talks about would lead to better predictions that are reliant on fewer assumptions and are less likely to mistake noise for signal. He also posits that many success stories in the world of prediction result from the application of Bayesian thinking (whether that is intentional or simply through intuition).

I would like to elaborate further on Bayesian reasoning, inference, and how it fits into the realm of machine learning in another post in the near future.

Criticisms

My main point on contention with Silver's point of view is the way that he positions the Bayesian methodology as wholly better than the frequentist alternative. While I would consider myself a Bayesian, I also understand that frequentist methods have their uses, particularly in cases where computational power is a limiting factor (Bayesian-based methods tend to be considerably more computationally intensive).

I take issue with the way he asserts that we should entirely replace frequentist methods with Bayesian alternatives as a way of dealing with issues inherent to the frequentist approach (misinterpreting p-values, p-values close to the cutoff, misinterpreting confidence intervals, etc.). I don't disagree that these are very real issues that come up quite often (and often lead to bad science), and that Bayesian methods could solve these issues. Unfortunately, the Bayesian approach is not without its own issues. The main criticism that can be brought against the methodology revolves around choice of the prior distribution, which can be viewed as overly arbitrary (and can lead to bad science when disingenuous choices are made). Since the Bayesian methodology is entirely focused on the process of using and updating beliefs, a choice of a very strong prior distribution can result in very inaccurate (unrepresentative or potentially even intentionally cherry-picked) results. On top of all this, frequentist and Bayesian methods are not even entirely mutually exclusive, and knowing when to use each can be a valuable skill in the field, regardless of which methodology you prefer (especially in machine learning contexts).

Silver also states that the only bad choice of prior belief is no belief. I wholly disagree with this as priors can be overly strong (as previously mentioned), or can be based on little to no evidence. In cases lacking adequate data--whether as a result of personal experience or other reasons--a choice of an uninformative prior would be the correct choice. Uninformative priors are types of prior distribution that are used in cases where we don't want to use any of our subjective beliefs and we want to make our Bayesian inferences as objectively as possible3.

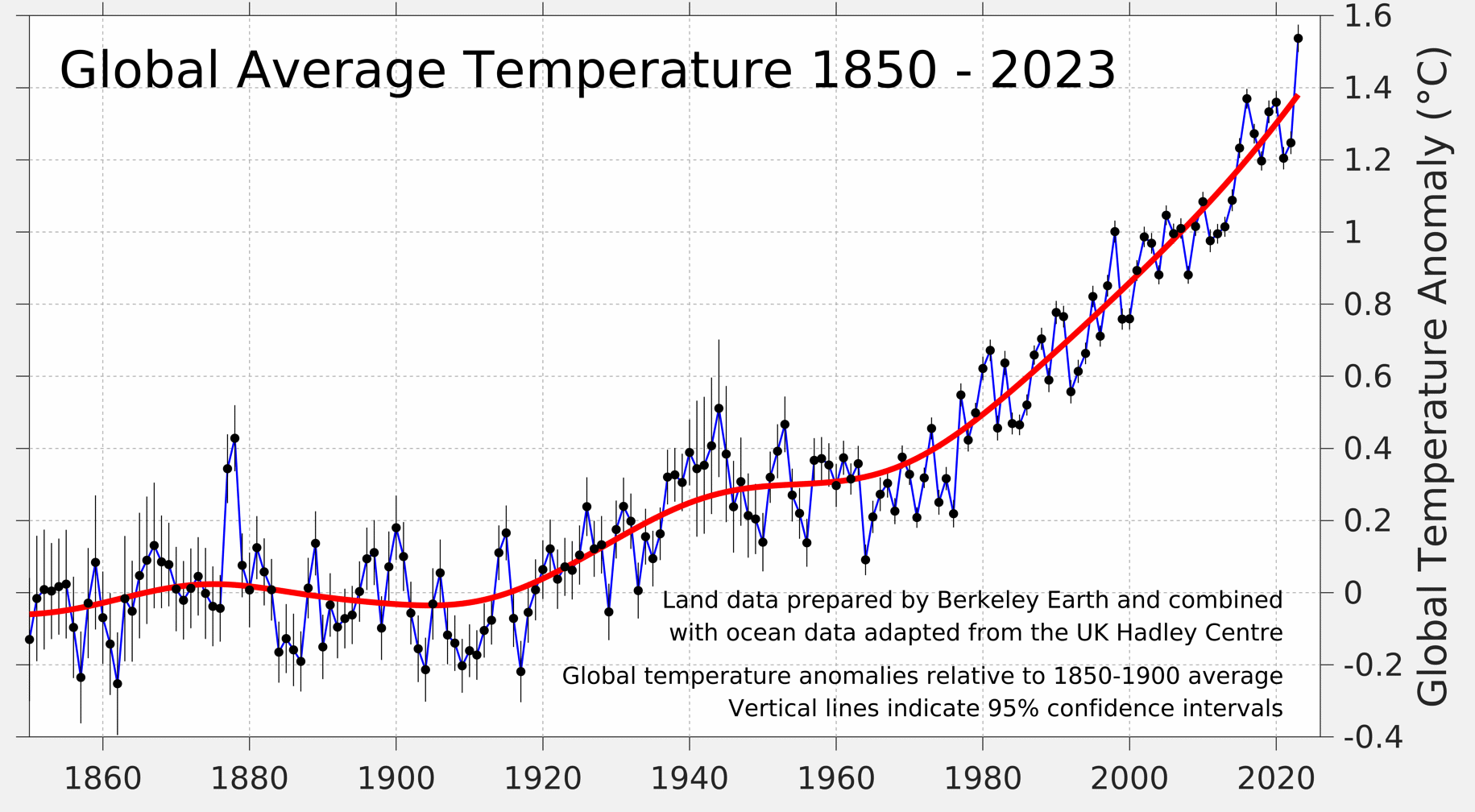

In one of the last case studies of the book, Silver discusses issues with climate modeling, as well as skepticism from experts and non-experts that result from models or their methodologies. This section includes a part where he compares models from two different sources, the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), and J. Scott Armstrong from the Heartland Institute (a conservative libertarian think tank). In this section of the book, Silver interviews Armstrong about his no-change model and his subsequent attempt to make a bet with Al Gore about the veracity of the IPCC model4. At the time (2013), Armstrong's no change model (2009) was performing better than the IPCC's climate model (2007)5 at predicting yearly change in global temperatures. The part of this I take issue with is how Silver heaps criticism onto the IPCC model about how it is overly complicated (which is partially true) and could be wrong, without applying any similar criticisms to Armstrong's model--a model produced by a conservative think tank with a history of producing dubious (and outright false) claims6. Silver didn't even raise the obvious criticism that the "no-change" model chose a baseline global temperature of the hottest year on record at the time, 19987.

I would consider this baseline choice as particularly egregious as (with the full context of the above graph), it ignores a century of increasing global temperatures in order to serve a political narrative. This stuck out to me, partially as a young person who cares a lot about climate change, but also because I read the previous sections of this exact book, in which Silver calls out pundits for making predictions that serve their narrative, and are often incorrect as a result. I don't believe that Nate Silver is a climate denier by any means, but I do think it was harmful that he perpetuated the climate skepticism narrative by not applying adequate scrutiny to Armstrong's model.

I do acknowledge that it has been more than a decade since this book was written, but in hindsight this section has aged quite poorly. As of 2024, we have had the three hottest years on record back to back, and the annual global temperature changes are much more in line with the IPCC than with Armstrong's no change model (which looks pretty bad now4). As climate change continues to grow worse, writings like this section of the book are damaging to momentum towards dealing with the issue.

Final Thoughts

As I said before, I really enjoyed this book and the case studies it investigates. I found the explanation of the Bayesian methodology and how it meshes well with human intuition very interesting, as well as how Silver seeks to apply it to create better predictions. Other than a couple of notable critiques, my thoughts on the book are entirely positive, and I would highly recommend it to anyone interested in statistics. My beliefs about frequentist and Bayesian statistics shifted a bit more towards the Bayesian side in light of the new data (this book).

At the end of it all, I found this book to be a very interesting read, and I will continue to follow Silver's work8 of modeling elections and more.

-

The Signal and The Noise - https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/305826/the-signal-and-the-noise-by-nate-silver/ ↩︎

-

Bayes Rules! An Introduction to Applied Bayesian Modeling - https://www.bayesrulesbook.com ↩︎

-

Uninformative priors - https://www.statlect.com/fundamentals-of-statistics/uninformative-prior ↩︎

-

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/349237629_The_Global_Warming_Challenge_Evidence-based_forecasting_for_climate_change_theclimatebetcom#fullTextFileContent ↩︎ ↩︎

-

IPCC report - https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/ar4_syr_full_report.pdf ↩︎

-

https://www.politifact.com/personalities/heartland-institute/ ↩︎

-

Change in global average temperature - https://berkeleyearth.org/global-temperature-report-for-2023/ ↩︎

-

Nate Silver's Silver Bulletin Blog - https://www.natesilver.net/ ↩︎

Loading comments...